The internal goals of your characters, their unconscious desires, are the hidden gems that provide your story with emotional weight.

Unlike an external goal which is front and centre to the plot, the internal goals of your characters are typically hidden for some portion of your story, if not from the audience, then from the characters themselves.

Ultimately, the internal goals of your characters are their unconscious needs which, once fulfilled, will make them truly happy.

Not every story will see its protagonist achieve their internal, unconscious goal. From Shakespearian stories such as Macbeth or Hamlet to modern screen stories such as Breaking Bad, characters failing to reach their internal goal is often what makes a tragedy.

A character’s internal goal is often related to their flaw, and in overcoming their flaw they achieve their unconscious, internal goal and become fulfilled.

The difference between an internal goal (unconscious need) and external goal (conscious want) is vividly shown in the classic film The Wizard of Oz.

Dorothy wants to be somewhere over the rainbow, this is her clear external goal. Her flaw is that she doesn’t appreciate what she already has.

Her internal goal or unconscious need (and the lesson she learns through the story) is to appreciate the love of those around her and that there is no place like home.

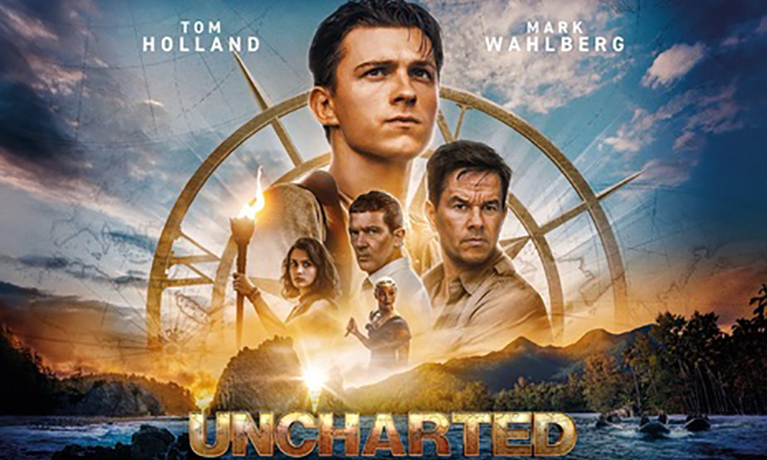

Uncharted: The Classic Adventure Story

With the simplistic external goals of wealth and finding Nathan Drake’s brother, Uncharted also presents more multifaceted internal goals for its protagonist, played by Tom Holland.

From the very first scene, the audience sees the two elements most important to Nathan Drake’s life: friendship (with his brother in the opening), and purpose as they discuss exploring the world.

When Victor comes to Nathan offering wealth and a chance to find his brother, the external goals of Nathan are clearly set. Yet unbeknownst to both characters, Victor was also setting out the protagonist’s internal goals for the story.

Having found Nathan a lonely and unhappy bartender and pickpocket, the audience can see his unconscious need for both a friend, and a sense of purpose in his life.

This is what Victor is truly offering him, even if both characters are unaware of it.

By the end of the movie [SPOILERS] neither external goal has truly been achieved for Nathan: his brother is dead, and the treasure and wealth are lost. Yet with joyous smiles and an upbeat musical score the credits roll on a happy ending.

This is, of course, because the internal goals of Nathan have been fulfilled. The theme of the movie was always about friendship and purpose, [read more about the importance of theme] and Nathan found both a friend in Victor, and his purpose while adventuring.

About Time: Internal Goals in a Romantic Comedy

As always, the external goals and internal goals of a protagonist are deeply intertwined, and this is especially true in Romantic Comedies such as About Time.

You could be forgiven for confusing Tim’s external goal of love for also being his internal goal, but it is not.

Though similar, it is clear from the very start that Tim’s true internal and unconscious need is to be happy. Unlike many other Romcoms, where love is not achieved until the very end scene where the story is resolved, About Time sees its two love interests Tim and Mary meet and fall in love relatively quickly.

Well within the first third of the story, Tim has seemingly achieved his primary external goal: he has found love, and by all accounts is doing a good job holding on to it.

So why doesn’t the movie end when they move in together? Or get married? Or even have children?

Although Tim is certainly a happy man throughout most of the screenplay, it is not until the very end, at the final turning point [read more about turning points], that Tim achieves his true internal need for happiness.

With a little wisdom from his passing father, and his own determination, the final turning point of About Time is Tim’s decision to not use his time travelling powers, and simply enjoy each day as if he was already reliving it. He learns to stop seeking perfection and to live in the moment.

By enjoying each day in all it’s unique glory, Tim finally achieves true happiness, and thus the credits roll as the protagonist’s internal goal is resolved.

Succession: The Complex Character Drama

Unpicking the internal and external character goals of ensemble dramas can be difficult. Although these dramas usually contain a central external goal for most of the main characters: escaping in Prison Break, or wealth and power in Succession, the internal goals are typically much more complex.

For more information on how to tackle writing an ensemble drama, read our Meet The Gang Part One and Part Two.

In the first season of Succession, Kendall, the son most likely to take over his father’s company, initially appears to be power hungry and ambitious.

Yet as the series progresses, and each move or decision is met with his father’s disapproval or beratement, Kendall’s true internal goal is revealed to the audience, though not necessarily to him.

It is not power or wealth that Kendall requires to be fulfilled as a person, but his father’s approval. In later seasons this is expanded to Kendall’s general insecurities, but in the first season his unconscious need for his father’s approval is crystal clear to the audience.

This internal goal of Kendall adds extra emotional weight to every scene between him and his father and helps to justify and explain every decision he makes in relation to the company.

Every time he seems out of his depth, or joyless in his job, the audience can refer back to his internal goal to understand why he does what he does.

Even by season three, this internal goal is not resolved, and in many ways, Kendall is one of many tragic characters in Succession. At it’s core Succession is about the corruption of wealth, and Kendall’s broken relationship with his father and siblings caused largely due to the pressures of wealth exemplifies this theme.

Character’s typically do not know their own internal goals, most often revealed to themselves only once achieving it, or in the case of tragic characters occasionally upon death.

The internal goals of your characters should be something they would only reveal on a therapist’s couch. Something that would take a lot of open thought and reflection to realise.

The silent force behind emotional tension and weight in your scenes, your character relationships, and especially all your character decisions, internal goals are the emotional lifeblood of your story.