“Show Don’t Tell”: What it Means and How to Apply It

Possibly one of the most famous tenets in all of visual media, “show don’t tell” is the principle of showing the viewer something, rather than explaining it through dialogue or narration.

Show Don’t Tell doesn’t just apply to one aspect of screenwriting but to several. It means actively dramatising character traits through action rather than description and dialogue. It also refers to externalising the internal; revealing what a character is thinking and feeling through their actions. ‘Show’ also refers to plot development through character choice.

With visual action comes dynamism. The screen is a visual medium, after all, and a character actively doing something (like saving the cat!) to indicate who they are and what they’re thinking is much more likely to leave a lasting impression on the audience.

Just as with real life, actions speak louder than words.

Showing Character

First impressions are important! A core aspect of any script or story are the characters in your world, and among the first things you’ll want to do is show to the audience who the characters are and what makes them unique.

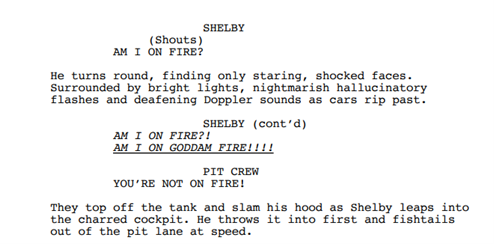

A great example is the introduction of Carroll Shelby in the opening of ‘Ford vs Ferrari’ (writers Jez Butterworth, John-Henry Butterworth, Jason Keller) . In the scene, Shelby comes into the pits to refuel during an important race, and exits the car on fire. After being doused by his pit crew, he immediately demands they refuel the car. They hesitate.

This one, very simple action of getting back in the race without hesitation powerfully shows the audience the core character traits of Mr Shelby. He is focused, brave, and most importantly, determined to win.

The action of Shelby immediately getting back in the race after being on fire is not only visually engaging, but energetic and informative as to the core traits of Shelby’s character. As the famous phrase goes: “seeing is believing”, and by seeing these qualities in Shelby, we believe it.

Externalising the Internal: Character Behaviour

Where novelists can write an entire paragraph on how the protagonist is feeling, as a screenwriter you have to be craftier. Monologues, voice-over and to-camera narration can be deployed on occasion, but for the most part you need to dramatize what the character is feeling and thinking, rather than having them explain.

This is not just to better hold the audience’s attention, but also to better represent real life: body language and visual cues are an important but often subconscious part of our everyday interactions. This often-overlooked aspect of storytelling helps build trust between the audience and the story, increasing the emotional impact of key scenes and moments.

One film that does this extremely well is ‘Hidden Figures’ (writers Allison Schroeder, Theodore Melfi, read script here). Set in 1960s America, the young, black mathematician Katherine Johnson struggles not only to aid NASA reach orbit, but also to work in place filled with people who seem to be disgusted by her very presence.

Many instances of racism and segregation are present throughout the movie, but one recurring item is the coffee pot – one for “coloured” people, and one for everyone else. When the “coloured” pot is missing, Katherine simply drinks from the normal one, drawing disdainful looks from her colleagues.

Heading back to her desk, Katherine looks down, holding her head low as the entire room stares at her. This subtle movement from Katherine tells us, the audience, everything we need to know about how she’s feeling – ostracized and oppressed. No dialogue about how bad racism is, just a small action that says so much more.

Furthering the Plot: Character Choices

Good plot is led by character choices. In the majority of situations, the best way to advance plot and increase the pace of your script is through action – in other words, people making active choices.

The movie ‘Whiplash’ (writer/director Damien Chazelle) encapsulates this aspect of visual storytelling perfectly with its crash scene. Neiman, the protagonist, is desperate to play on stage, and is racing to the venue with the drumsticks he had previously forgotten to bring. Because of his jittery driving, Neiman crashes and the car flips.

Now he’s got a choice: Neiman gets out of the car, dazed and bloodied and immediately starts a wobbly run towards the venue to play. Neiman makes the clear and very active choice that getting on stage is more important than tending to his injuries, driving the plot forward in an active way.

Neiman’s crash not only serves as an obstacle on his journey to stardom, thus progressing the plot, but also shows the nature of Neiman as an obsessed artist. The best scripts will have many scenes that serve multiple purposes: a character’s action will not only reveal their personality, but will also progress plot all in a short and active scene.

To “show not tell” means to make the audience feel the information you’re giving them, rather than just knowing it. A sure-fire way to improve any script, showing rather than telling will bring more emotional weight and visceral impact to each and every scene it’s used in.