I’ve tended to focus in this series on personality models which emphasise how different we all are, as it’s generally the differences between characters which lead to drama. But let’s break the rule for the last in the series and look at a model which says we are all exactly the same when it comes to responding to a change in our circumstances – and which creates drama through a battle we have with our own psyche.

If you’re doing your job as a writer, your characters will spend a lot of time wrestling with some kind of change: losing a job, getting a job, receiving bad news, meeting a new partner, finishing with an existing partner, having an accident, being betrayed… Without change there is no drama. And our ability to understand the impact of change on a person comes from the “transition curve”, courtesy of a doctor who took one of the most dramatic changes of all – dealing with a diagnosis of terminal illness – and used it to map how we respond to any change.

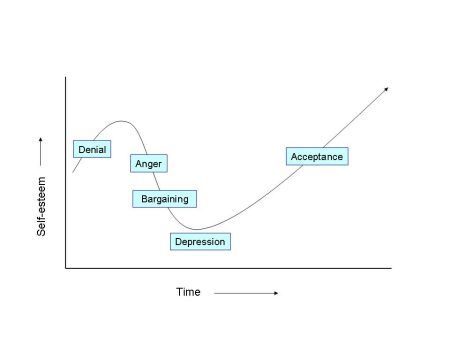

Elizabeth Kubler-Ross made extensive studies of the reactions of terminally ill patients on learning the facts about their condition. When she put her observations together, she found that each and every terminally ill individual went through a series of identifiable stages in the process of coping, or attempting to cope, with the reality of death. If you were to plot the stages over time, and graph them according to how positive one feels, you get the curve below.

After a brief period of shock, you see that the curve goes upwards. How can such bad news result in a positive reaction? The answer is that the positive feelings are essentially self-deluding, for this is the stage of Denial. The stance here is ‘It isn’t true: the tests must be wrong; I’ve never felt better.’

After a brief period of shock, you see that the curve goes upwards. How can such bad news result in a positive reaction? The answer is that the positive feelings are essentially self-deluding, for this is the stage of Denial. The stance here is ‘It isn’t true: the tests must be wrong; I’ve never felt better.’

If the patient can be convinced of the reality of the situation, this positive stance is wiped out at a stroke and the patient advances quickly to the next stage, Anger. This is emotion born of frustration and impotence, and all logic is abandoned, before a semblance of apparent logic returns in the stage of Bargaining. The archetypal example of Bargaining is doing a deal with God (“Cure me and I’ll do good deeds for the rest of my life”). And when Bargaining doesn’t work, then Depression takes over (“I can’t cope with this, I might as well give up now.”)

If the patient can be coaxed beyond this, they reach the point of Acceptance, the point at which one decides to face what is happening and use the remainder of one’s time positively. This will require some experimentation, until the truly positive final step is achieved and the patient has a way of living which is authentic and embraces their condition.

Notice anything, narrative structure enthusiasts? Is this not a little like the arc of a character through a story? Is the stage of Acceptance not unlike that moment at the end of Act Two (or Act Four, if you’re trying to impress the new head of BBC Drama) when a character accepts the need to change and sets off to make what s/he has learned about him- or herself work? Does the Denial stage not bear a passing resemblance to the “refusal of the call” stage of the Hero’s Journey? Because what does a good story do if not present your protagonist with an enforced change, and then watch how they come to terms with it? This is why the transition curve is so powerful – it connects us with a deep human truth which unites us all, and which is reflected in stories told throughout history.

But before you start making all your characters terminally ill, this curve applies to any change, even positive ones. What does every lottery winner say? “This win won’t change me” (while you smugly think “hah, you’ve clearly never read about Denial being the first reaction to change – you’re going to suffer, mother****er”. Or maybe that’s just me). It doesn’t even have to be used in the service of Drama. Sitcoms rely heavily on Denial, Anger and Bargaining stages: The battle against the need to change is a staple of British comedy, from One Foot In The Grave to Fawlty Towers. Of course in a sitcom the character mustn’t change, so they are doomed never to reach Acceptance.

A comedy told as a complete story, though, will go through the whole curve. In the recent Melissa McCarthy vehicle Spy Rick Ford (Jason Statham), the alpha male obsessive foreign agent, is driven first by Denial (ignoring the rule to stay out of the mission), then Anger (becoming more and more of a loose cannon), Bargaining (as he tries to make an unnecessary partnership with Susan Cooper work) and finally, the Acceptance that Susan has done a good job. We leave him experimenting with a new phase as… I won’t spoil the ending for you. RomComs are another great example: the characters spend much of the film in Denial, Anger or Bargaining, as they each resist the call to change represented by their relationship antagonist. The film’s crisis is the point where they must Accept their need for each other, whereupon one of them runs to the airport and… you get the point.

So whatever genre you work in, ensuring that no character experiences change without triggering the transition curve will bring great authenticity to your script. And don’t only think about the major change that runs through the arc of the story; within one block of dialogue, if it’s doing its job properly, a character will be pushed out of his or her comfort zone and will inevitably display at least some Denial, pushing back to try and preserve the status quo.

This is my last blog in the series – but like any human being, I will go straight to Denial and do another farewell one shortly.

Phil Lowe is a scriptwriter and novelist with a professional background in business psychology. http://www.phil-lowe.com. Follow him on Twitter @grumpyrabbit.