Every writer – alright, apart from Steven Moffat – has a day job; mine is as a management coach and facilitator, using psychological models to help people not just perform at their best, but also – to give one example – deal with conflict in the workplace. Even if your only experience of psychometric testing is completing a “What Kind of Best Friend Are You?” questionnaire in Just Seventeen magazine, you get the idea (I’m “Dependable Listener”, by the way).

As a writer, I use the same models to create characters who are not just authentic, but who are most likely to create drama when they encounter someone who is fundamentally different from them in some way.

Today I’m going to give you a whistle-stop tour of the Strengths Deployment Inventory, a questionnaire which helps identify someone’s primary motivation and how it might bring them into conflict with others. Oh, and because the world of business psychology, like writing, is big on Reputation, I have to do a quick health warning. Please don’t use this model to psychoanalyse your friends (not to their faces, anyway). I’m giving you a simplistic version on the understanding you will only let loose your embryonic knowledge on people who are fictional.

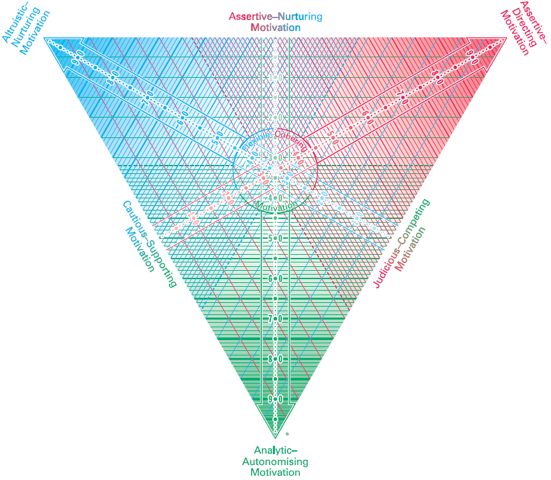

The SDI comes from the work of Elias Porter. Its underlying principle is: the primary motive of all human beings is a desire to feel worthwhile about ourselves. The reason life is so rich and dramatic is that we all try to feel worthwhile in different ways, according to our “motivational value system” (I’ll use MVS from here on). Porter plotted three primary – and potentially mutually exclusive – MVSs in the corners of the chart below:

You will see three distinct colours, plus some blends to take care of the rich variety of human personality. For simplicity, let’s start with the basics. Imagine you give your character this questionnaire and they come out as pure Blue, Green or Red. What does that mean?

Blue is known as the “Altruistic-Nurturing” MVS. This character feels worthwhile when they are taking care of others, contributing to the growth or welfare of individuals or groups. If other people feel good, they feel good too.

Red is “Assertive-Directing”. This character feels worthwhile when they are getting concrete results; they have an achievement orientation, and are comfortable taking the lead.

Green is called the “Analytic-Autonomising” MVS. Detached, analytical, individualistic; this character prizes logic and systematic thinking.

For convenience, imagine you have three main characters in your story, one of each colour. Here’s where you create conflict, and so drama. There’s a recent example in the BBC TV series The Missing. Tony Hughes is pure Red, driving forward in unrelenting pursuit of a result. Wait, though; surely any parent of a missing child would do that? Well his wife Emily doesn’t; she’s Green. Her impulse is to step back and proceed with caution, trusting that the system will work. Add in a Blue detective, Julien, who wants to take care of Tony, and our protagonist is repeatedly blocked from two sources: his wife seems detached and uncaring, and the detective keeps stopping him acting on impulse in case he makes things worse for himself.

But before you excitedly start writing pure colours into your story, take a breath and consider how easily we fall into tropes: nurses are Blue, soldiers are Red, boffins are Green (and always played by Benedict Cumberbatch). You can cut across this in three ways:

1) Choose an unlikely colour. A Blue accountant is much more interesting than a Green one. Writing an action hero? Obviously Red, right? Except one thing that made Die Hard so successful is that McLane, our hero, is motivated not by a drive to beat the competition but to mend a broken relationship. Granted, Bruce Willis doesn’t do a lot of visible nurturing in the movie (“Yippee-ki-yay, if that doesn’t cause you too much inconvenience, motherf***er!”) but he has a Blue heart.

2) Have the character behave contrary to stereotype. Motivation is a fixed anchor, but the way a character behaves in its pursuit may vary. If your character is Green, don’t feel obliged to copy the kind of ‘route one’ behaviour exhibited by Mr Spock. How about Victor Meldrew in the sitcom One Foot In The Grave? What does he want? The same thing as Spock: to be left alone in a world where everything works as expected. (Wouldn’t Spock be much more interesting if he unexpectedly erupted: “I don’t believe it!!”? OK, maybe not, but you get the point.)

3) Blend in other colours: 99% of human beings are not a pure colour: we can be 50:50 blends (as illustrated on the triangle); in a zone between the three (known as The Hub, where the motivator is to be flexible to the needs of everyone else); or Dulux style, Green with a hint of Red/Blue. (In The Missing, the mainly Blue Julien Baptiste also has a hint of Red: he can’t let go of a case he couldn’t solve.) This gives you some inner conflict as well: how does the character resolve conflicting motivators?

All drama is conflict, allegedly, so make sure you share the colours around. Of course it’s de rigeur to have an antagonist of a different hue (and, in the case of RomComs and Bromances, your relationship antagonist is almost certain to have an opposite MVS) – but how about your protagonist’s ally? Inspector Morse was pure Green, so his sidekick Lewis was Blue. When Lewis got his own series, quelle surprise: he got a Green sidekick.

And don’t forget, your character is still allowed to change. Maybe a Blue learns how to behave a little more Red in order to stand up for what they believe in. Maybe when under pressure a Red’s motivation shifts – they stop pushing forward and turn Green, withdrawing to think things through and get the idea which helps them win. Or maybe they don’t change, hanging on to what has made them feel good in the past: the Blue may go all out to look after others, the Red becomes more competitive, and so on – this is what we call an “overdone strength” (polite way of saying “weakness”). At the crisis point, what is your character’s instinct: fight (Red), submit (Blue) or run away (Green)?

As a professional practitioner I am obliged to point out: other psychological models are available. As with narrative structure theories, it’s horses for courses. But the SDI can give you a quick and easy way of auditing the potential for conflict – or at least variety – between your fledgling characters. Happy colouring!

The Strengths Deployment Inventory is published and licensed by www.personalstrengths.com

Phil Lowe is a scriptwriter and novelist. He originally trained and worked as an actor and has a professional background in business psychology. www.phil-lowe.com