A great film or tv show keeps us watching and one of the main techniques you can use to achieve this is by continuously raising questions throughout your script.

We stay with a story because we want to find out more, to know what happens next. It’s most obviously deployed in the genres that pose one big and obvious question up front; mystery (crime, murder, investigation), thriller and horror, with the latter two often posing the question “will they survive?”.

We want to stay watching to discover how the murderer is caught or whether our favourite character survives the night. But in a great character drama, we will be just as invested in knowing if a character we’re rooting for will find happiness, or save their marriage, or find the courage to walk away from a toxic relationship.

Raising questions from the opening pages

The first pages of your script are critical. In order to both hook your audience and get noticed by a script reader, your script must create intrigue and leave the audience wanting to know more.

The questions can be explicit: “who is the murderer?” or “what is the antagonist planning?”. Or they can be implicit, where new ideas, half-reveals or strange events pique our curiosity.

The 2005 film Lord of War written by Andrew Niccol does both.

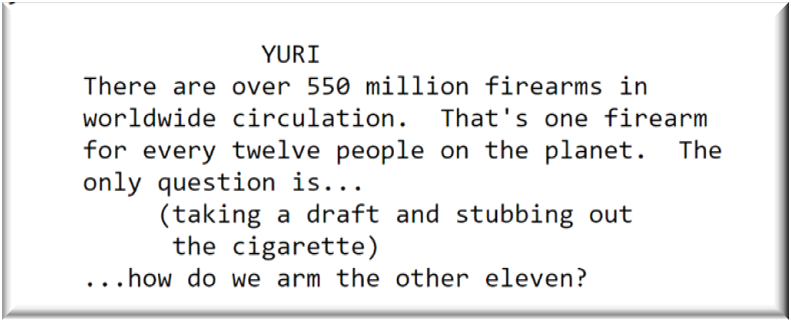

In the very first scene, the camera pans to a smartly dressed businessman (Yuri, played by Nicholas Cage), stood in a battle-ravaged street. Clearly not a military man nor a normal civilian, this incongruent and surprising image immediately begs the question: where is he, who is he, and why is he there? Yuri turns to the camera and says…

We’re immediately curious and wondering, who is this man who wants to arm the whole world, and want will he do to try and achieve it?

In less than a minute of screentime character has been revealed, multiple questions have been asked both implicitly and explicitly, and the audience is hooked.

But you don’t need something startling or incongruent to hook your audience from the start. Small reveals that pose more questions can be equally effective. The art of hooking the audience while establishing your story can be seen clearly in Silver Linings Playbook, which we explore in more detail in our article ‘How to Hook Your Audience in the First Ten Pages.

Raising questions for the characters

Most easily identified in crime and murder mystery stories such as Broadchurch or Bodyguard, raising questions for the characters to answer drives plot by creating a problem to be solved. And if our character wants to know an answer, we want to discover it too.

The same technique can be just as effective in character-driven drama. Building on the sensational success of the first film, Frozen 2 is a movie centred around questions. From beginning to end, they drive the plot as Elsa seeks to unravel the mystery of where the ghostly voice is coming from.

As Elsa confronts questions of her heritage and powers, driving the main plot, both Anna and Christoph get some much-needed time to ask their own questions about who they are. When Anna rushes off without Christoph to save her sister, he asks the question: “what am I really doing here?”. The playful ballad Lost in the Woods allows him to ask this question both to himself and the audience, creating a deeper personal connection to the character.

Anna gets a similar moment to shine later in the movie. After spending the last movie and a half rushing into danger, things seem all but lost. What does she do when everything seems hopeless? Who is she without her sister? A crucial moment of character development, these questions allow Anna to push through her loss and become more independent with the song The Next Right Thing, mirroring that of Christoph’s journey earlier in the film.

With the audience hooked and desperate to discover more about your characters and their story, it’s important to keep the ball rolling. Each story beat should either heighten previous questions raised or introduce new ones. If the identity of the antagonist is revealed, the next question raised could be “why are they doing this?”.

Raising questions for the audience

You can also raise questions for the audience that the characters know the answers to, by withholding information and again, making the audience want to find out more.

Written by Eric Heisserer, Arrival is a masterpiece of storytelling, with layers upon layers of questions constantly evolving throughout the screenplay. With every beat new questions are raised and information is seeded throughout to setup later plot developments. As Amy Adams’ character Louise Banks investigates an alien arrival, questions for the characters to answer such as “who are the aliens?” and “what do they want?” initially drive the plot.

In addition, Heisserer withholds information about the details of Louise Bank’s life to create added intrigue. Moments such as the out of place scenes with Banks’ daughter raise questions of “where is her daughter, why doesn’t she mention her daughter in this crisis situation, isn’t she worried about her?”.

Eventually, this culminates in (Spoilers!) the reveal that what was assumed to be Adams’ past is actually her future, revealed to her by the aliens that see time in a non-linear way.

Even upon resolving Arrival’s main questions, Heisserer provokes interesting questions about the nature of time, through a mastery of non-linear storytelling. You can read more about non-linear storytelling techniques here.

Raising questions but avoiding confusion

It is important to remember “everything in moderation”. Raising questions to create intrigue is important, with too little leaving an audience bored. However, withholding too much information can create confusion.

Keeping your audience orientated is critical. If they’ve no clue what’s going in, they’re likely to give up. How willing to feel adrift your audience are will play a big part in how commercial or art-house your work is perceived to be.

Your characters and your audience only know what you choose to reveal to them, so use this technique of raising questions, big and small, to keep your audience hooked throughout your story.