Creating conflict is the key to any story. As a script progresses, it is important to constantly test and challenge your characters, giving them hard decisions and tough paths to take. This conflict often manifests in the form of an external threat – the white walkers in ‘Game of Thrones’, for example. Yet there are many different types of conflict, both in life and on screen, and the best scripts will explore multiple different types of conflict.

External and internal conflict can both drive a script, and are often best utilised when melded together to explore character and develop plot. Both types of conflict have nuanced subcategories, with some being more prominent in particular genres. Yet no matter what, it is important that conflict not only appears in your script, but it is also used as an effective tool to develop character, move plot, create tension, and advance your storytelling.

External: Environmental

External conflict is often the most visible form of conflict, driving plot and informing character decisions, and it can come in many different forms. One of the oldest and most primal forms of conflict is that of environmental conflict. The human struggle against nature, to survive against a power much greater than us.

True stories such as ‘127 Hours’ or ‘Everest’ often include environmental conflict as the main driver of plot and action. Environmental conflict is not limited to true stories, however; ‘The Martian’ is an excellent example of fictional environmental conflict, where the story is driven almost entirely by the protagonist Mark’s will to survive against the harsh and unforgiving environment of Mars.

External: Societal

Societal conflict can also play a major role in driving story, in particular with bildungsroman (coming of age) stories. The pressures of society, cultural norms, parental pressures, and expectations from peers and colleagues provide an excellent catalyst of conflict to develop character and story.

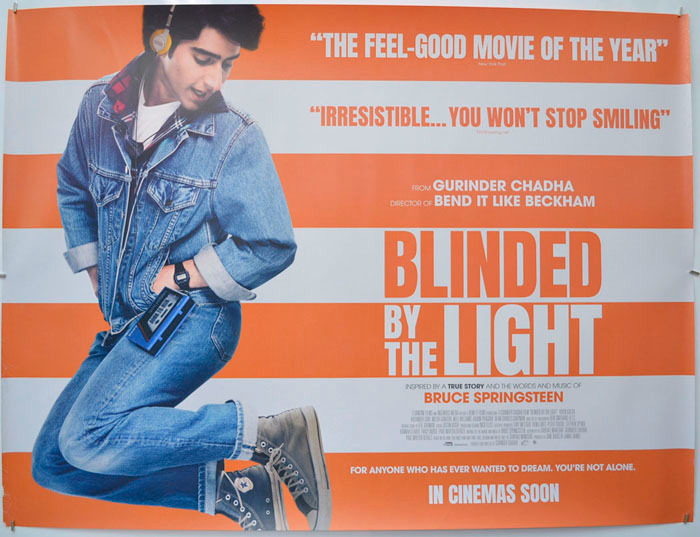

This is done brilliantly in Gurinder Chadha’s ‘Blinded by the Light’, in which Javed must face the cultural expectations of his father, the racial inequalities he faces as a young Pakistani teen in 1980s Britain, and the economic pressures of coming from a working-class, immigrant family.

In this, a range of different societal expectations come into conflict with Javed’s interests and personality, forcing him to fight to discover who he is, and who he wants to be. Javed’s conflict with different societal norms is not simply a fight for the sake of being different, but one that shapes his attitudes towards his passion (writing) and his relationships with family and friends.

External: Interpersonal

The core of all drama, interpersonal conflicts are the backbone of many great character-based stories, and will appear in some form in almost every script. Our relationships with others define us, and conflict within those relationships can be used to shape character and develop story.

One of the most famous relationships ever put to screen is that of Luke and Darth Vader in the original ‘Star Wars’ trilogy. Despite being a space opera epic about war and politics, it is this relationship that truly defines Luke’s story throughout the trilogy, with Luke defining his moral code in direct opposition to that of his father.

Interpersonal conflict is also found in ensemble multi-protagonist stories such as ‘Downtown Abbey’ or ‘Bridgerton’, and in these character-dramas interpersonal conflict takes centre-stage.

In ‘Bridgerton’, a core element of the plot is the conflict between the Featherington and Bridgerton girls to find suitors, as well as a multitude of different relationships and connections between characters ebbing and flowing in the story.

From romance to comedy, and even in action and sci-fi, interpersonal relationships and conflict play a key role in challenging the characters and driving plot.

Internal

Often the most overlooked form of conflict in scriptwriting, internal conflict is a vital part of character development and defining motives in a story. While some screenplays do have an internal conflict at their core such as ‘A Beautiful Mind’ or ‘The Sopranos’, conflict within a character can be found in a multitude of stories.

As demonstrated by the famous scenes between Tony (a mob boss) and his therapist, at the core of ‘The Sopranos’ is Tony’s internal conflict between being the man he wants to be – a family man, and the man he must be to run a criminal organisation.

In season six, Tony learns one of his men (Vito) is gay, and his whole crew and other crime families want him dead because of it. In a scene in episode six, Tony discusses the issue with his therapist, allowing the audience to see his moral dilemma.

Initially, Tony goes on a homophobic rant – the sort of thing his crew would expect him to say. As the scene goes on, it becomes clear that Tony actually has no issue with Vito’s sexuality, but feels he must both talk and act homophobically in order to maintain control of his criminal empire. By the end of the scene, Tony concedes that “I had a second chance, why shouldn’t he?”.

He is riddled with internal conflict, having to decide between being the man he wants to be – one who is understanding and considerate, and the man he feels he has to be – one who is ruthless and powerful.

On a smaller scale, internal conflict can also come at turning points in a story, where a character must struggle internally with a choice. This is demonstrated often in ‘The Expanse’, with one particular scene bringing James Holden (one of the protagonists) a choice; allow a medical relief ship to flee, possibly carrying a harmful and contagious bioweapon onboard, or shoot down the innocent aid workers. ‘The Expanse’ explores these decisions to powerful effect, with each tough internal conflict taking a toll on the characters, and often shifting their own moral code and outlook on the world.

Most stories will contain a multitude of different forms of conflict, and the best will seamlessly blend them together into a natural element of their story telling and world building. Conflict is a necessary and useful tool in every screenwriter’s arsenal, moving plot forward and developing characters and relationships, all while providing an opportunity to explore wider topics and themes at play in your script.