I agreed to take on this blog post with some trepidation. Why? Because, in my opinion, script structure is a hot potato of “How to…” blogging. It’s like religion; those who subscribe to a system will doggedly defend their beliefs, and “structure atheists” who insist that there is no structure in their stories won’t be tempted either.

Not only that, but structure is my personal nemesis. Of all the storytelling elements, it’s the one that can lurk under still waters of pithy dialogue, good characterisation and entertaining story in a script. It is often the problem when I delve into something that “isn’t quite working properly”. It’s the one that many writers find the least instinctive when working on their stories, and it’s taken me years of reading to get a handle on it. I feel like it’s time to settle the score on script structure.

There are many ways to skin (and Save) The Cat

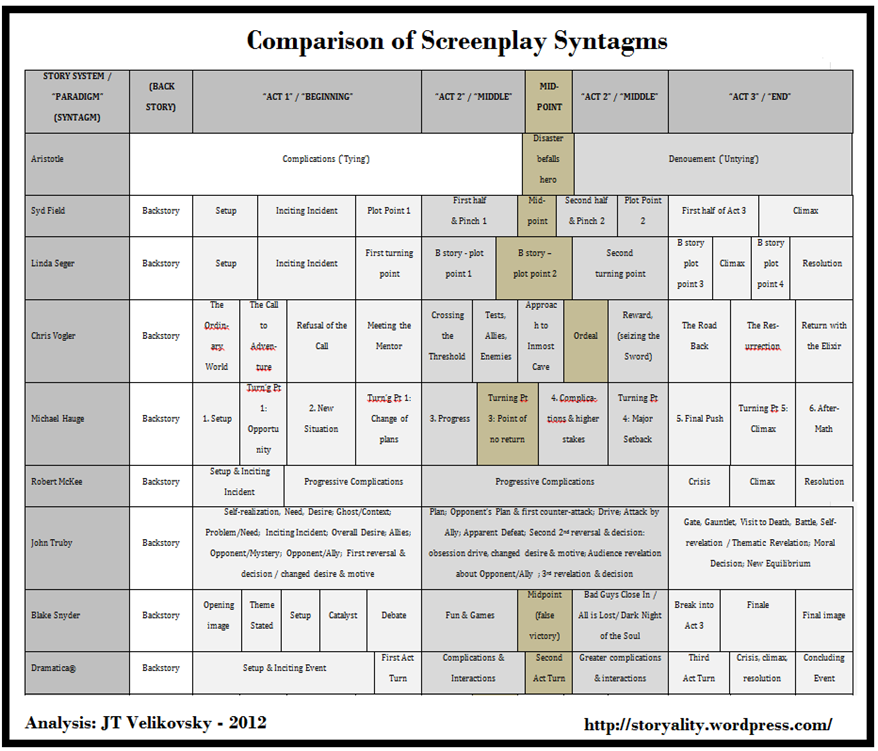

Go to Google Image Search and type in “screenplay structure”; the various structure diagrams can look like something from a Dan Brown novel. This can give the impression that schools of thought on structure are vastly different. However, this simple but brilliant diagram by JT Velikovsky (himself the creator of StoryAlity, the result of his doctoral thesis into screenwriting) breaks down the terminology and templates used by different schools of thought on screenplay structure.

It’s interesting, laid out visually, to see as many similarities as well as the differences. So are they worth reading if they’re all saying something similar? Absolutely.

Story gurus, or indeed any take on screenplay structure, show a ‘way in’ to storytelling. Although different gurus will have different emphases on certain aspects of story, or may have a different writing style, the more you read the more attuned you’ll be to how stories are crafted.

Making structure work for you

Another worry that newer writers have about structure is that it limits creativity. This needn’t be the case. Scott Myer’s brilliant blog Go Into The Story uses the pithy slogan “tools, not rules” to approach story structure – and I second that as a way of learning to love structure.

Structure helps provide both logic to the storytelling, and emotion in presenting events in a meaningful context. The key is that the structure must work to the premise / idea you want to tell, rather than letting the structure dictate the story.

Here are some ways in which films have made the structure work for their particular story:

Work your structure around your concept: Annie Hall and the Usual Suspects are structured by a character remembering events, meaning that relevant parts of story can be told out of order to intrigue – but not confuse – the audience. Four Weddings and a Funeral structures its story around the events of five ceremonies. Memento tells a story about memory in reverse segments from end to beginning, consistently undermining what we know of the characters with each reveal of what’s come before.

Moving the elements around: Brad Johnson’s article in ScriptMag magazine brilliantly illustrates this point, using two films that fit the necessary story moments in Act I, but execute them in very different ways. Back To The Future’s first act involves a lengthy set-up of Marty’s home, school and love life that exceeds the usual ‘rule’ of an early inciting incident (usually around page 10). However, when the Inciting Incident does come – the terrorists arrive to steal the plutonium from Marty and Doc Brown – both Marty and the story are ready within a couple of pages to make a quick leap to travel back in time and delve into Act II. The Hobbit, by contrast, has an early Inciting Incident – the dwarves and Gandalf arriving at Bilbo’s house – but a longer period of resistance (some critics say too long…) before Bilbo is ready to accept his journey. If you want to read more on this the article is here.

Is structure always to blame? Sometimes when something ‘feels wrong’ in a script, we think that the structure isn’t working in the story, when occasionally it can actually be structure’s way of showing you that there’s a better, cleverer way to deliver your story point. Whilst it’s still true that the structure should fit the story you want to tell in the majority of cases (see above), here’s a recent example of the reverse in practise:

A writer wanted to take a character on a long central journey, but wasn’t quite sure how to deliver the ending. After back and forth on some interesting ideas they’d come up with, we looked back at the structure of their first act, which was really strong, and how mirroring those beats in the final sequence would underline the character change. This helped the writer decide not only where they wanted the character to end up, but also to create a satisfying ending. Voila – an example of structure helping story!

Obviously this hasn’t even scratched the surface of structure in film and TV, so over the coming weeks Hayley, myself and other guest post writers will delve back into this and other topics for the Writer’s Toolbox series – articles you can use to improve your craft as a writer. Stay tuned…

But in the meantime, Joe William’s post gives some of the differences between writing for film and TV and touches on structure – check it out here.